The American government (Democrats & Republicans) basically decided that low prices were more important to the economy than jobs. This Edward McClellend piece in salon will walk you through the whole sick history. Read the whole thing.

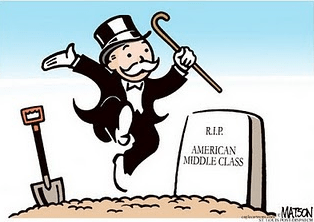

When I was growing up, it was assumed that America’s shared prosperity was the natural endpoint of our economy’s development, that capitalism had produced the workers paradise to which Communism unsuccessfully aspired. Now, with the perspective of 40 years, it’s obvious that the nonstop economic expansion that lasted from the end of World War II to the Arab oil embargo of 1973 was a historical fluke, made possible by the fact that the United States was the only country to emerge from that war with its industrial capacity intact. Unfortunately, the middle class – especially the blue-collar middle class – is also starting to look like a fluke, an interlude between Gilded Ages that more closely reflects the way most societies structure themselves economically. For the majority of human history – and in the majority of countries today – there have been only two classes: aristocracy and peasantry. It’s an order in which the many toil for subsistence wages to provide luxuries for the few. Twentieth century America temporarily escaped this stratification, but now, as statistics on economic inequality demonstrate, we’re slipping back in that direction. Between 1970 and today, the share of the nation’s income that went to the middle class – households earning two-thirds to double the national median – fell from 62 percent to 45 percent. Last year, the wealthiest 1 percent took in 19 percent of America’s income – their highest share since 1928. It’s as though the New Deal and the modern labor movement never happened.

The shrinking of the middle class is not a failure of capitalism. It’s a failure of government. Capitalism has been doing exactly what it was designed to do: concentrating wealth in the ownership class, while providing the mass of workers with just enough wages to feed, house and clothe themselves. Young people who graduate from college to $9.80 an hour jobs as sales clerks or data processors are giving up on the concept of employment as a vehicle for improving their financial fortunes: In a recent survey, 24 percent defined the American dream as “not being in debt.” They’re not trying to get ahead. They’re just trying to get to zero.

That’s the natural drift of the relationship between capital and labor, and it can only be arrested by an activist government that chooses to step in as a referee. The organizing victories that founded the modern union movement were made possible by the National Labor Relations Act, a piece of New Deal legislation guaranteeing workers the right to bargain collectively. The plotters of the 1936-37 Flint Sit Down Strike, which gave birth to the United Auto Workers, tried to time their action to coincide with the inauguration of Frank Murphy, Michigan’s newly elected New Deal governor. Murphy dispatched the National Guard to Flint, but instead of ordering his guardsmen to throw the workers out of the plants, as he legally could have done, he ordered them to ensure the workers remained safely inside. The strike resulted in a nickel an hour raise and an end to arbitrary firings. It guaranteed the success of the UAW, whose high wages and benefits set the standard for American workers for the next 45 years.